The Apostrophe Blog

A few years ago, a graduate school friend who now teaches in a low-residency writing program was working on a panel about “Late Bloomers” for the Associated Writing Program’s annual conference. As I understood it, the idea was to gather a group of writers and/or teachers and lead a discussion about people who come to their writing careers and/or get published and recognized after they are forty years old. At the time, our back-and-forth e-mails got me thinking about what such a term means, and whether or not it really is applicable to the many of us who embrace writing and the writing life—whether for the first time or after a long hiatus—when we are “middle-aged.”

To me, the word “late” itself implies time passing—as does the word blooming—as if there is a before-and-after, an inevitable progression, almost a prescription as to how something—an event, an activity, a life—is expected to unfold. A flower follows a cycle, buds then blooms and, in time, the blossom drops and dies. Beginning and end. Start then finish. Early versus late. In a recent essay in the New Yorker called “Late Bloomers”, Malcolm Gladwell, writes: “Genius, in the popular conception, is inextricably tied up with precocity—doing something truly creative, we’re inclined to think, requires the freshness and exuberance and energy of youth.” He goes on to offer a few familiar examples—Mozart, Picasso, Orson Welles. But the story doesn’t stop there.

These days, it certainly seems that, for the most part, contemporary literary culture celebrates the precocious achievements of gifted youth more often than seasoned later-in-life talents. I wonder, instead, if it isn’t a better idea to see creativity and art as part of the flow of life and our lives, something we inhabit and do, a continuous, unfolding arc of possibility rather than an arrival at a destination bound and determined solely by our subjective notions of time?

For a host of reasons, many of us take longer to do what we want or feel we are meant to do in life. I returned to a focus on writing at in 1988 when I was in my early 30s; that seems young now, looking back. I moved on from extramural classes to the master’s program at SUNY/Binghamton, getting my degree in 1994. But only in my 40s, after other life priorities shifted and changed, was I able to make writing my daily focus. And still that journey has included more workshops, classes, and writing teachers and mentors. Surely, life intervenes time and again and circumstances and artistic preoccupations change, even for those writers who start out of the gate running, showing flash and dazzle when they are twenty-five years old.

Are the potholes any different for a late-blooming writer than a youngster? Maybe, maybe not. Sometimes I think there are more potholes the farther away you live from New York City or if you are outside the college and university writing scene, as I have chosen to be. Still, I think an increasing number of writers (not just later-in-life ones) are doing their work outside of academia. Many can’t afford to plunk down the tuition money for MFA/MA programs. Or they aren’t willing to go into debt for a degree that won’t necessarily get them very much in terms of practical, wage-earning skills in the end. This may make it even harder to market oneself, or to break into the journals especially the ones associated with colleges and universities—we all know connections are the name of the game in that corner of the writing world.

I also wonder if publication a good way to measure who is and isn’t arriving to the writer’s life late. Publishing is a major crapshoot. I have had some success in my “late-blooming period” (a fellowship, publications, a chapbook.) Still, these successes, while encouraging, are a reminder that the competition to be “discovered” let alone successfully published—and read by more than your friends and relatives, books not immediately remaindered, etc.—is fierce. Some of this is a direct result of the industry the AWP itself has worked to create—so many writing programs which has led to many more writers at a time when fewer and fewer people are reading and buying books. The longer I work at this (and possibly the older I get) I find I am writing more for myself and less for any hope of recognition or the attentive eyes of the world. I know young writers who’ve come to this same conclusion. We do it for the love or because we can’t not write. And hope to find a few readers along the way who like and appreciate our work. After that it was all gravy, every minute of it, as Raymond Carver once wrote in a poem. (Carver died at the age of 50 in 1988. Most of his writing success came to him after he was 40 years old.)

More and more, I suspect blooming only happens when we stop talking about whether it’s early or late. When we stop comparing our idiosyncratic creative trajectories tit for tat. When we simply sit down and do the work, our work. In the end, isn’t that all that really matters?

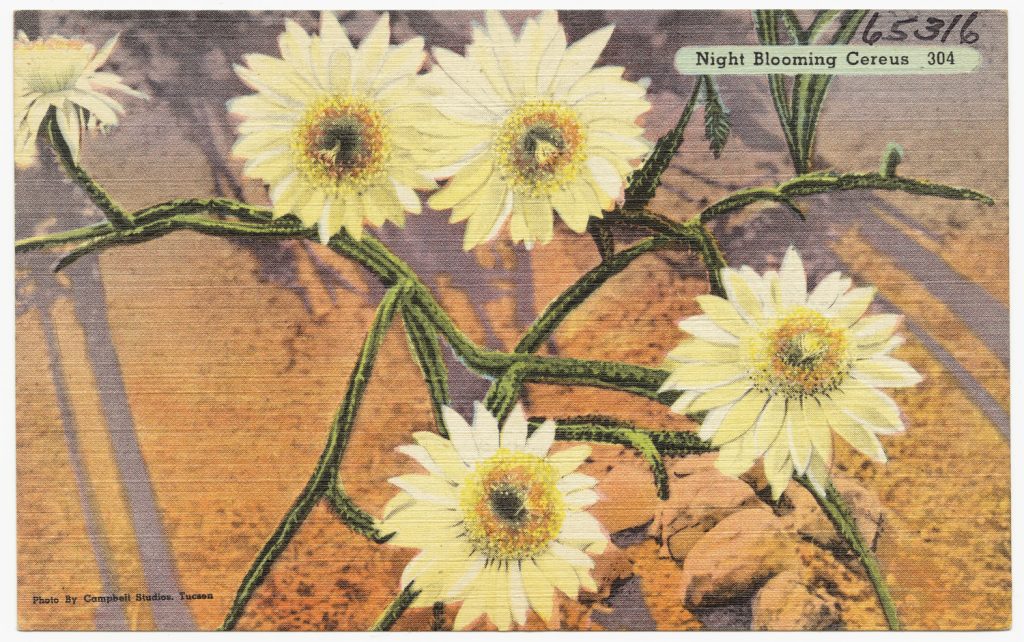

The public domain image at the top of this post is of an 1871 oil painting by Martin Johnson Heade entitled “Study of a Night-Blooming Cereus.” And a postscript for all you horticulture nerds: the Night-blooming Cereus is a member of the cactus family that blossoms only once, its heady and fragrant petals closing by the following morning. It’s also known (with good reason) as Queen of the Night, the lunar flower, the moon flower, and luna flower.

| 1930s Postcard of Five Blooms of Night-Blooming Cereus |

- Published but Uncollected: “My Bikini Goes to Goodwill” - June 17, 2025

- So Much Beauty… - May 27, 2025

- Blank Verse: Old-Fashioned Yet Modern - May 25, 2025