Combing through my archives of writing today and found this in the Anthracite Diaries section of my old blog, Stream of Consciousness. It’s a brief essay about being in my hometown on September 11, 2001 after being in New York City visiting my adult son the day before, September 10th. I guess everyone has their stories of where they were that day. Maybe writers more so? Here’s one of mine.

COMFORT

I grew up in Plymouth, a town of 6500 on the Susquehanna River in Northeastern Pennsylvania. The only person in my immediate family who’s ever left, I lived two hours “up the road” in Ithaca, New York for nineteen years before moving across the country to the Pacific Northwest in 1998.

Whenever I go home, I draw the curtain on the person I am the rest of the time in the rest of my life—fretting, churning, striving—and try my best to enter into Plymouth’s small town pace: more 19th century than 21st, a place where everyone seems to know everyone else. Church bells chime the hour every day of the week not just Sundays, a comfort more than an aural reminder that I’m wasting my day, or my life. Few things are considered urgent or done with more than a single motivation or purpose. A walk along the dike is a walk along the dike, not the requisite twenty-minutes-three-times-a-week so you’ll have a healthy heart. The blue plastic tarp roped to a hole in the side of a restaurant damaged by fire ten years before is part of the landscape instead of an eyesore. When I ask why the tarp’s still there, everyone knows the story—how the owner never got the insurance money, if he never fixes it, maybe he’ll get a HUD grant instead.

I was home, visiting family, when four hijacked airplanes crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and a field in southwestern Pennsylvania on September 11, 2001. Plymouth is barely 100 miles as the crow flies from New York City, where I’d been until the night before helping my 24-year old college student son set up his new apartment in Staten Island. I’d planned to stay until the 11th but we’d finished our chores ahead of schedule, my son had schoolwork to do, and it was muggy and hot. I said goodbye, knowing I’d see my son the following week on my way home to Oregon, and pointed my rental car toward the Jersey turnpike. I missed rush hour but not the storm that made the next day cool and clear.

That Tuesday morning I woke up early. My parents were out of town, visiting my mother’s sister in southern New Jersey so I had the house to myself. I was having my second cup of coffee when one of my sisters called from work to tell me to turn on the T.V. The first tower had just been hit.

The calm of my life one second before metamorphosed into an urgency of smoke, fire, and dread, seeping out of the television into my parent’s living room, spilling blood on the floor, pouring into the streets of Plymouth like the ’72 Agnes flood. My first call was to my still-sleeping husband in Oregon. Then I dialed my son in New York on my parents’ rotary phone. I dialed over and over, 20, 30, 40 times and heard “all circuits busy” again and again and again. I finally got through to my son’s girlfriend and left a message with her before all lines into the city went dead.

My other sister had the day off. She and her four year old son drove over from where they live, across the river in south Wilkes-Barre. They picked up tuna hoagies from Red’s Subs and we ate lunch soldered to the news. The bottom edge of every local station crawled with emergency information: I-80 and I-81 closed to all traffic; the whereabouts of the Martz Bus commuters who left Public Square every weekday before dawn for Wall Street; classes at the community college cancelled, the YMCA day care letting out early, no evening novenas for the St. Ignatius Ladies Sodality. My nephew played with the only toy he could find in my parents’ house: a set of wooden blocks that used to belong to my son. He built a tower out of the blue squares and orange rectangles, balanced an unstable red arch on top, then sat back and waited for blocks to fall.

Eventually my sister left and I took a break from the relentlessness of the news on T.V. I got in my rental car, the idea being to fill the gas tank just in case I had to drive somewhere in the next day or two. But where? To New York City to rescue my son, stranded now by a moat of closed bridges and roads? The 2400 miles back to Oregon, my speedy getaway from the crazy, targeted East?

The few stores still in business on Plymouth’s Main Street had closed for the day, including the state-run store that sells liquor and wine. I got gas and kept driving, through town and south down US Route 11. Piles of wasted coal and dirt bike trails filled the land between the highway and the river. I passed a front lawn used car lot, the National Guard Armory built on the site where anthracite was first mined in 1807, the boarded-up Stoney’s Tavern, a repair shop called Mister Brakes.

Right before the junction with PA 29, I decided to turn around. I pulled off the road at the spot where a blue and gold Pennsylvania historical marker commemorating the Avondale Mine disaster had been planted in the coal and ash that serves as road shoulder in that part of the world. Even though the marker was easy to read from the front seat of the car, I got out anyway.

“ON SEPTEMBER 6, 1869, A FIRE BROKE OUT AT THE NEARBY AVONDALE COLLIERY, TRAPPING THE MINERS. THE EVENTUAL DEATH TOLL WAS 110. THIS INCLUDED FIVEBOYS BETWEEN THE AGES OF TWELVE AND SEVENTEEN, AND TWO VOLUNTEERS WHO WERE

SUFFOCATED WHILE ATTEMPTING RESCUE. AS A RESULT OF THIS DISASTER, PENNSYLVANIA’S GENERAL ASSEMBLY ENACTED LEGISLATION IN 1870 WHICH WAS DESIGNED TO ENFORCE GREATER SAFETY IN THE INDUSTRY.”

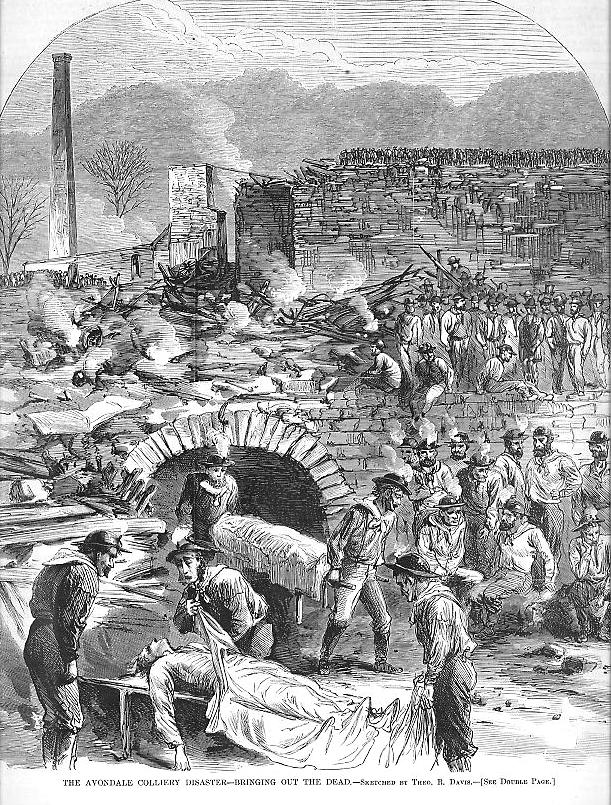

What the marker didn’t say—what I knew from research for a novel I was once writing—was that the Avondale fire was the first and only time Plymouth made the international news. Avondale was considered the anthracite industry’s first major disaster. It had been the first day back to work for the miners after a long, bitterly feuded strike. Headlines claimed that the civilized world woke up that morning and was shocked by news of the conflagration. There was public outrage at the danger the miners had been put in by the coal breaker’s faulty design. Harper’s published a long article complete with lithographed renderings of the grisly scene. People from all over the world sent money to the relief fund for victims’ families, over $150,000. I think someone even wrote a song to memorialize the catastrophic event.

Amazing as it seems, they recovered all the bodies. Passageways were flooded and many of the openings to the undamaged chambers in the mine’s convoluted maze were blocked by fallen timber and smoldering debris. When rescuers could finally descend the shaft, they found the bodies of old men with young boys by their feet, nesting like lambs, and others, heads bent, their hands clasped, the tips of their fingers black. One newspaper told how two miners, David Williams and his cousin Eddie, looked like they were boxing. They were brought to the surface as they’d been found, stiff, with both arms raised and fists clenched, asphyxiated while they swung at the air.

I stood in front of the historical marker, a September day 132 years later, and stared at the words “Avondale Hill” painted in hasty, yellow letters on a cement wall across the highway. Below the words, a white arrow pointed in the direction of a one-lane road that snaked up to what surely was the old breaker site.

I thought about my son in New York, my stepdaughter who’d just moved to D.C., my parents driving back from New Jersey hurtling toward shut down roads. I thought about David and Eddie Williams, wondered if their mothers saw when they lifted their bodies out of the shaft. And I thought about what I’d seen on television earlier in the day, footage—captured unexpectedly and shown only once—of people leaping from the Trade Center windows, their bodies falling, weighted feathers, and how more than a few were two people holding hands. I got back into the car, pulled into the right lane, and followed the arrow, a sharp, angled left. The sun was high in the sky when I opened the car door and tiptoed into a flat, grassy field on the top of Avondale Hill. There were many hours of church bells to go before that day would reach its end.

The public domain image at the top of this post by Theo Davis is entitled “Bringing out the dead”. It was originally published in the September 25, 1869 issue of Harper’s Weekly.

- Greetings from War-Ravaged Portland! - October 5, 2025

- Publication Day: America’s Slide Towards Authoritarianism from IHRAM Press - October 1, 2025

- Autumnal Equinox & the Diminishing Hours of Light… - September 26, 2025