The Apostrophe Blog

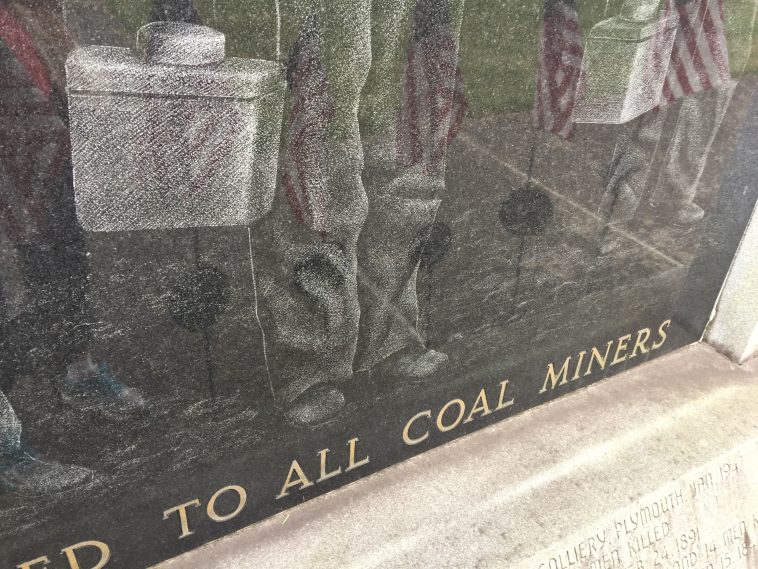

My chapbook, Eternity a Coal’s Throw, was published by Burning River Press of Cleveland, Ohio in 2012. Chris Bowen, the editor, had a very interesting process for making his chapbooks stand out from the crowd. Each one included an introductory essay that talked about a bit about the “how” and the “why” that led to the writing of that particular group of poems. In my case, this collection was all about the place I grew up, the anthracite coal country of northeastern Pennsylvania.

Below is an excerpt from what I came up with for inclusion in my little chapbook of six poems which includes one of my personal favorites, “Ode to My Hometown Whose Mascot Is a Human Kielbasa Wearing a Sleeping Bag With Armholes & Flip-Flops.”

Introductory Essay for Eternity a Coal’s Throw

Something happened here. In your life there are a few places, or maybe only the one place,where something happened, and then there are all the other places. —Alice Munro

Once upon a time—when I was another person, it often seems—here’s how I began an overly ambitious novel (still in progress): “You could be born in a place, live there long and never really know what it meant. No matter if you walked the mountains and climbed to the tops of trees, taking in the broadest view. Or drove a tunnel deep in the earth finishing miles from where you began. In the end, you’d only find wildness and another dark and hidden spot.”

Two decades later, with these poems in Eternity a Coal’s Throw, I am attempting to shine yet another patch of light on the anthracite coal country along the Susquehanna River where I was born and grew up.

Northeastern Pennsylvania in the 1960s, the era I came of age, was an economically and culturally depressed area. One of fifty-three counties formally defined as Appalachia by the Appalachian Regional Commission, it boasted the highest levels of both unemployment and welfare recipients in the entire state. Good students (and I was one) were supposed to grow up and play it safe, whether out in the workforce or off to college before returning home to settle for a decent job, a spouse, a family, a modest house on a small-town street. By the age of ten, I knew I’d be one of the ones who had to leave; at the time, of course, I didn’t know just how far I’d have to go.

Since 1973, I’ve mostly “lived away” as the local idiom describes it. Two years of college in Oberlin, Ohio. A brief return home (long story, that) before hightailing it 125 miles “up the road” to Ithaca, New York in 1979. Then, in 1998, fleeing clear across the continent to the Pacific Northwest to live nine years in the Coast Range foothills and, since 2007, in a city of two rivers, Portland.

[…]But there is something about that northeastern Pennsylvania place—the mining-wrecked landscape; its century of post-industrial impoverishment; its beaten-down but oddly resilient, near-to-beautiful dishevelment; the ties that bind the many people who stay as well as the many who leave only to return; the crazy quilt stitched together out of dozens of immigrant cultures; the still reliable generations of kinship, friendship, heartfelt community—well, all my life, it has both mocked and bedeviled me.

[…]Writing these poems, I invited a kind of blood memory of it all—from the slag heaps to the treeless streets and subsiding backyards, potato pancakes and a Main Street of too many beer gardens, heaved bricks and crooked-marker cemeteries filled with rows of my dead relatives, the burning underground mine fires and our 1972 Hurricane Agnes flood—to dance a “Pennsylvania Polka” with my words.

[…]In these poems, I’ve tried my personal version of deep-vein mining and come back to the surface, sooty and gasping for air. I’ve sought to engineer a reclamation of lost voices, of forgotten stories and lives, some of them connected by kinship to my own. To connect that dotted, hollowed landscape and its people, my people, with the person I left behind, the prodigal I often feel I am, the displaced person I have clearly become.

Like the anthracite outcrops first discovered by the Susquehannocks, these humble (and flawed) offerings are but surface revelations of a place that’s forever buried inside me—my impossible, inescapable geological and cultural DNA—complicated and labyrinthine as its latticework of underground mines. It’s now time to let the poetry (and the mystery) be.

- Don’t Fence Me In! - July 5, 2025

- Nothing to Celebrate Today… - July 4, 2025

- Call It By Its Name - July 2, 2025